“I’m either really stupid or lucky,” I thought to myself.

I was on a mountain bike, pedaling my way over the Portachuelo Pass at approximately 15,700 feet, and I hadn’t seen a single soul on this dirt road; outside lone car, and my guide about a 500 meters back, in his old Suziki 4×4.

We had come back to Peru 10 days before to adopt a small, Calico mountain dog we met several months ago – which is a whole other story – and while my wife was bonding with our new boy, I decided to explore.

I enjoy pushing my limits physically and mentally, and this weekend’s 150km loop around Huascaran National Park in Peru is among the most challenging and risky adventures I’ve taken in a while.

Wherever I looked were features to a magnitude that’s difficult to explain: mountains surpassing 22,000 feet, glaciers with huge, visible crevasses, an immesnse valley several thousand feet below, and a single lane road, which had no guardrails, and at times drops of hundreds of feet.

While nerve-racking, I ultimately put myself in this situation. As with snowboarding in difficult terrain, there’s just one way down, and simply need to point your tips and let gravity take over.

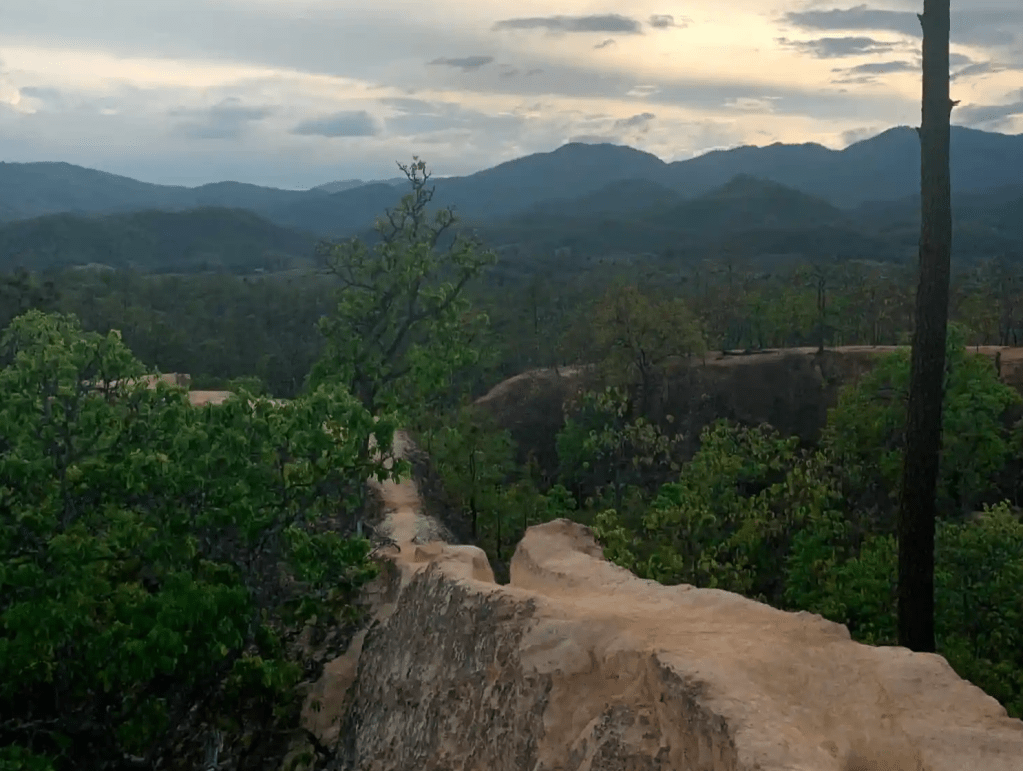

Photo Doesn’t Capture the Magnitude of this Mountain

*****

There’s something about traveling that can allow more accessible adventuring than the rigidness and sometimes gatekeeping attitude that can be found in the U.S.

For the most part, the U.S. coddles people looking to explore or have fun, especially when you consider the rest of the world. As you move West towards Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming, there is more of a laissez-faire approach, but the litigious nature of the country creates an environment with bumpers in the gutter.

I’d still bowl an 11.

Almost two decades ago, while studying in Beijing, my friends and I deemed these differences in regulations, or lack thereof, as “China Safe.” This is by no means a knock at China, nor any other country, but in fact it shows you a more Do What Thou Will attitude than in the U.S.

In other countries, you can find yourself wondering….

Do I want to hike in the mountains of Yunnan after a three-foot snowstorm and zero gear?

Sure.

Do I want to walk across the narrow stone bridges of the Pai Canyon, where slipping on a 12” land bridge means a likely fatal tumble to the valley?

Go nuts.

Picture courtesy of this blog

Is it possible to rent a motorcycle with no safety checks on either rider abilities or the bikes’ mechanics, and drive through the mountains of Vietnam?

Of course you can.

Should I spend the weekend hiking across desolate areas of the Great Wall of China, making sure I don’t fall off the crumbling stairs to the rocky terrain below, and camp in the abandoned guard towers?

Okay, well, you probably can’t do that today.

The point being, is that you can do a lot of risky things across the world, but in most places outside of the U.S., the risk is entirely on you. You can do what you choose, but if something goes wrong, even if there are emergency agencies available, logistically it can prove very difficult to get rescued.

I think that sometimes, this can be the biggest misunderstanding of people when they go to a less developed country.

*****

Several months ago, a Brazilian woman tragically died while trying to summit Mount Rinjani volcano in Indonesia. Unfortunately, there were a lot of actions of negligence that could have prevented this – first and foremost the guide not leaving her behind when she couldn’t keep up. The reality of the situation however, there are much looser safety regulations and protocols in Indonesia.

Ultimately, and while it is disputed how, she fell into the volcano, and after several days she died, whether from injuries sustained during the fall, dehydration, or the elements. There was a lot of uproar across social media about the Indonesian government not doing enough to save her, while the realities of the situation were much more intricate.

While the island itself is populated, the logistics of rescue are complicated. The volcano has over a 12,000 prominence, that is, a 12,000 vertical ascent from the ocean – no small feat in climbing. To those that ask ‘Can’t they use a helicopter,’ regardless of whether or not the island has a helicopter, you need a specialized helicopter to ascend to those altitudes.

All in all, you need to be comfortable with the risks that you’re taking, and what happens if the situation goes south.

*****

After about five hours of riding, partly through rain and hail – it was reminiscent of playing soccer in the cold spring rain growing up in Western Pennsylvania – we found ourselves in the small town of Yanama.

Few tourists come here, and as such the infrastructure is poor. There was a single store to grab a cold Cusquena (the locals prefer it warm), and we drank as we waited to watch the sun slip behind the snow-capped Cordillera Blancas.

My guide, Mauro, and I were chatting away, and he shared that the following year, all the roads we were riding through would begin to be paved, thanks to the Belt and Road Initiatives (BRI) of the People’s Republic of China. If you’re unfamiliar, the BRI has been going on since 2013 as a key directive of Xi Jinping.

It follows as such: The government of China, or ‘private’ Chinese companies, find an initiative such as building a highway, for a developing country, finance the project, provide the manpower and equipment, complete the project, and the country now has better means to transport goods, people, etc. thereby increasing the economic output of the area.

While these initiatives are technically loans with interest, the real payback is China gaining access and influence to these nations. Now, being an American, I certainly cannot point fingers at other countries wanting global influence, but I’ve seen this show before.

While in Laos in 2017, there were many conversations about the BRI’s Boten-Vientiane railroad. With near constant delays for over a decade, corruption, village displacement, and ecological damage, it was eventually completed. Similar to NAFTA, this was under the guise of progress, and affluence for all, when in reality there were a select few that benefited (mainly China and Thailand), and the people of one of the poorest countries now indebted to one of the wealthiest.

Why does Yanama and Peru need this? Part of the beauty of traveling is that it’s difficult, which in turn can create a more isolated, and thereby unique experience. There are countless photos tagged #laguna69 or #rainbowmountain making it appear as though the photos weren’t taken with hundreds or thousands of other people waiting to get their next Instagram Reel.

We were lucky enough to see Llaca in solitude

It’s a conflicting feeling, and one that I feel is all too true in liberal America. We have ours – money, safety, well-being – and we believe that you <insert any developing country>, should keep yourself pristine and free from development, progress be damned.

As we walked back to our hostel, there was a large banner that was falling off a fence. Mauro held up the sign so I could get a good look. Super-imposed on the muddy road I just biked down was a lowed pixelated image of two-lane highway. In a few years, will this still be the thrilling, isolated adventure it was today?

We both sighed.

****

The following day, the weather was ominous as we were approaching a pass. This was the highest pass in Peru, with a 1.5km tunnel cutting through the mountain I had to pedal through on a paved two-lane highway. While infrequent, semi-trucks slowly crept up one side of the pass and sped down the other.

I asked my guide “With the rain and fog, is this dangerous?”

He looked at me. “Oh, yes. There are a lot more accidents in this weather.”

My nerves had me, hands shaking and my breath was rapid and irregular. Was this the altitude, or was I having a panick attack?

I began my ascent, and from the time I entered the tunnel to passing through the other side felt like an enterity.

While I thought the most difficult part was over, I was met was even worse rain and fog hugging the top 500 meters of the other side of the pass. I began my descent, trying not to notice the crosses and small chapels the size of doll houses, a stark reminder of what can happen on these roads if you stop paying attention even for a second.

The next two hours were high-intensity riding, with more than a few close calls, mainly due to the driving culture of Peru and greater Latin America – essentially, “I’ve got nowhere to be but I’m in a rush – now get out of my way.”

As I got closer to the valley, the weather cleared, but I remained focused as often that can be the most dangerous part of the trip.

The last few kilometers, cows took over the road, and I smiled as I manuevered around them.

So, was I really stupid, or lucky?

While at times I bit off more than I expected, I believe that I was incredibly lucky to have this experience. At the same time, I’m smart enough to know when to pack it in for awhile. As I texted my friend on the ride back to Huaraz, “I’m done with my risky adventures for awhile. Give me a beach and a beer.”

Leave a comment