Genocide.

This is a word that, in today’s environment, conjures up division.

For some, the term and its application have strict, defined parameters. Others may find its use as a way to draw attention to a cause. And still, others may simply use the term and apply it to call out any injustice in the world, diluting the gravity of the word.

Over the last century, the world has seen numerous genocides and countless tragedies, regardless of their definition. A few include:

The Holocaust, where five to seven million, or 2/3s of European Jews, were systematically murdered under the Third Reich.

The Rwandan genocide of 70% of the Tutsi population over a 100-day period, where people were often butchered with machetes.

The Cambodian genocide of the Khmer Rouge, where chaos reigned supreme, and the world turned a blind eye, leading to at least 1.4 million people, or 15% of the population, finding their last day in the Killing Fields.

All of these events are horrific displays of what humanity is capable of, but thankfully, all of the atrocities were stopped before the complete annihilation of a people.

It was not until recently, upon our trip to Patagonia, that we learned of the Selk’nam genocide, where it is estimated that over 90% of the people were exterminated.

What happens when a people are almost entirely erased from history?

*****

The winds were blowing when we arrived at the Strait of Magellan. We were in hour two of a 12-hour bus ride, waiting for the winds to die down so we could ferry five kilometers to Tierra del Fuego, and make our way to our last stop on our Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego trip, Ushuaia.

We had started our bus journey to Ushuaia from Punta Arenas, where we spent a day at a hotel overlooking the Strait. From our hotel, we saw freighter ships fighting the blow, salty wisps of water dancing and seemingly enveloping these ships as they inched across the water, somehow.

I remembered reading about the Strait of Magellan, specifically how dangerous it was, and today, on the 50th anniversary of the sinking of the Edmond Fitzgerald, I couldn’t help but wonder how and why they ever attempted this passage.

When we were finally able to board the ferry, I went to a protected part of the ship and looked at the water below. There was no single direction the water was moving, just a turbulent barrier to one of the most unforgiving archipelagos on the planet.

*****

Tierra del Fuego – the Land of Fire – was first seen by the then-modern world during Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition, which set sail in 1520. It was given this name because of the numerous fires, built by the native inhabitants, that could be seen from the ships. Magellan and his men did not attempt to land, for a likely unwarranted fear that the natives were waiting to ambush his men. They sailed on, for a time.

While there were small explorations and contact made with the indigenous groups on the islands, it wasn’t until 1855 that a permanent settlement in the form of a Christian mission and the demise of a people – the Selk’nam – began.

*****

The bus ride provides ample time to think.

The land shifts, slowly at first, then seemingly all at once, from a barren steppe to rugged, forested mountain terrain, with fallen trees everywhere, due to the shallow soil and high winds. A fallen tree may decompose in a few years in more temperate climates, but here, the harsh conditions prevent bacteria, and it’s estimated that trees can take over a millennium to fully decompose.

Winding through the valleys and surrounded by mountains, some are rounded as if a hand moved over a mound of sand at the beach. This difference in mountain peaks – rounded versus pointed – denotes the glacial line: in the last ice age, the glacier’s depth was approximately 1,000 meters, and anything below that height was ground down, under the sheer weight of the sheets.

There are no people, save for the cars, trucks, buses, and motorcycles passing, but you’re still reminded of the human presence by fence barriers denoting property, even cutting through lakes, rivers, and ponds.

Why?

*****

The Christian missions, regardless of their true intentions, began a series of events that would be tragic for the Selk’nam.

In the latter part of the 1800s, settlers began arriving, many from Italy and Croatia, and were soon granted estancias, or ranches, from the Argentinian and Chilean governments. Between the settlers killing the native Guanaco (from my research and conversations, I cannot be certain if this was strategic to deprive the Selk’nam of their primary food source), and establishing borders of their property for their sheep to graze, the settlers significantly disrupted the way of life of the Selk’nam.

Having no concept of private property, the Selk’nam began to hunt the sheep, and between this and supposed violent skirmishes, ranchers were given carte blanche to do what they saw fit.

Many ranchers used this new authority and perceived immunity to finance violent campaigns to eliminate the Selk’nam. These campaigns began with ears as proof of death, then hands, and finally skulls, as it was inferred that these hired guns were ‘gaming the system’ and not truly killing them, at first. A dead woman was worth more than a man.

Julius Popper, profiteer and main culprit of the genocide, posed over a Selk’nam corpse

Enterprises in the area, such as the Company for the Exploitation of Tierra del Fuego, did their best to hide these activities from their shareholders.

When all was said and done, it’s estimated that 3,500 of the 4,000 Selk’nam were murdered between 1880 – 1900. Shortly after, there was a trial that confirmed not only were the Selk’nam hunted, but they were also kidnapped and relocated throughout Chile and Argentina.

Ultimately, a few farmers and authorities were found to be at fault, but were never jailed, as the presiding judge claimed that the Selk’nam account couldn’t be put into record, as there were no translators. This was a lie.

In the following years, while supposed good-faith efforts were made by Salesian missionaries, to preserve their culture, much had been irreparably lost, and by 1920 it was estimated that between 100-200 Selk’nam were left.

Ángela Loij, the last known Selk’nam, died in May 1974.

*****

As I began to learn about the Selk’nam, I quickly surmised that I would most likely not get the full story of these people. How do you find the truth when history itself is lost?

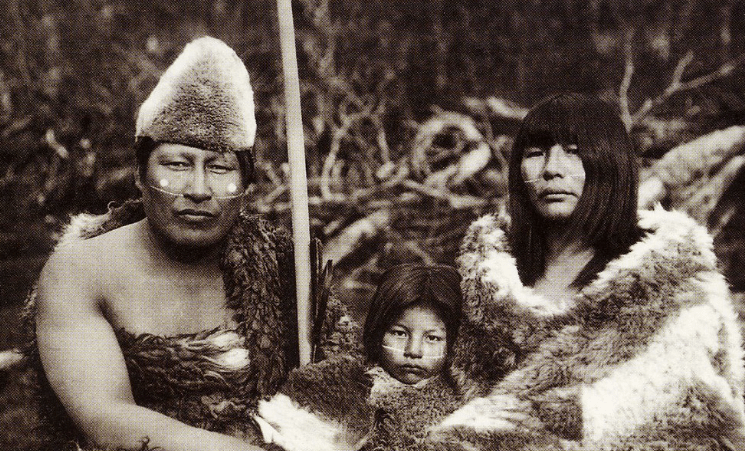

The Selk’nam arrived in Tierra del Fuego thousands of years ago and shared the land with several other groups. Why they chose this harsh land is anyone’s guess, but they were able to thrive in the environment.

Even with the extremes in temperature, the Selk’nam chose to remain relatively naked, with some reports stating that the groups in Tierra del Fuego would cover themselves in animal grease for added protection against the wind. In the harshest weather, they would also use Guanaco furs.

They were described by many as giants, with the average height of over six feet, although this cannot be verified, and I am unsure if this is tied to a biblical Nephilim lore from the European settlers.

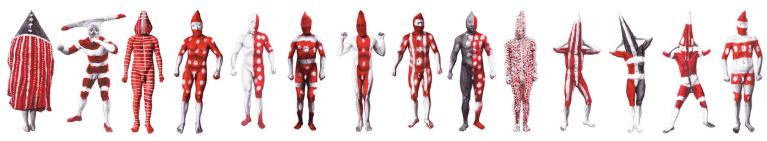

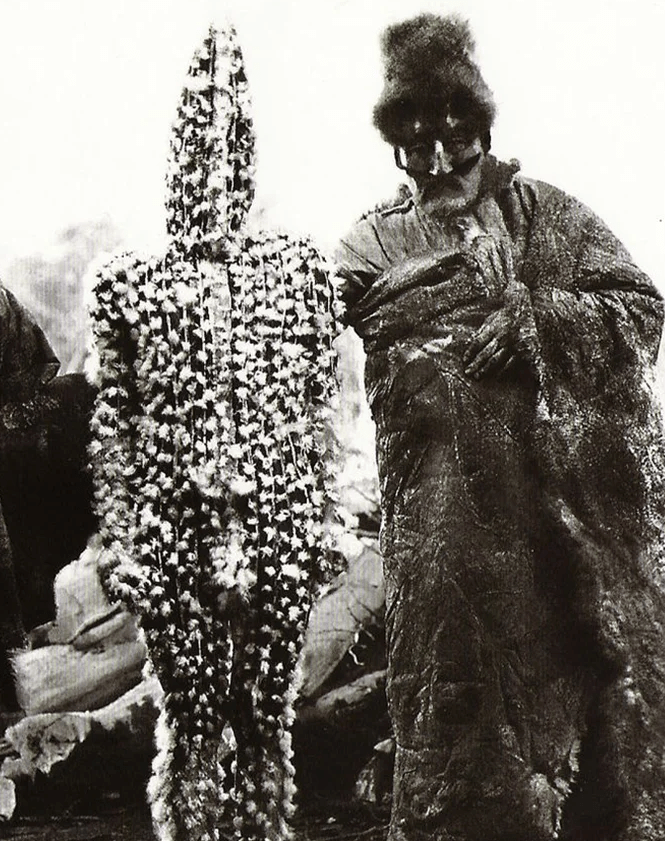

One of the more intriguing cultural elements of the Selk’nam was the ceremonies surrounding the rights of passage from young boys into manhood, the Hain. As there is not a singular story, I will try to relay my understanding in a condensed and hopefully accurate format.

The Hain was a rigorous process for boys to become men, often occurring over many months in the wintertime. Some research suggests that during years with better stores of food, the Hain would last longer, as this would allow the men to leave camp for extended periods of time, as the women did not hunt.

The Selk’nam had a rich culture of numerous spirits, each with their own personality that played a key role in the Hain.

Towards the end of the Hain, and one of the final rituals, the men would dress up as spirits and battle the boys, in part to impress and scare the women. An interesting aspect of this ritual, at least to my understanding, was that this was done in a very wink-wink, nudge-nudge way, where the women pretended they didn’t know it wasn’t an act.

*****

As the warmth of the day quickly faded into a deep chill in Ushuaia, I thought of the men and women who seemed impervious to this brutal climate. A place once called home to the Selk’nam, now a tourist destination. Many of the sheep are gone now, but the ranches remain, with some having signs or statues of Selk’nam spirits, and many symbols of the Selk’nam dot the town.

The people who lived here for millennia now seem like a footnote or side attraction, with few people being able to rattle off more than a few sentences about them.

*****

On September 5th, 2023, the Chilean government finally recognized the Selk’nam people as one of the 11 indigenous tribes in Chile. This comes after the 2017 census, where 1,144 people identified as Selk’nam, children and grandchildren of people forced into adoptions and scattered throughout Chile.

While their future is unknown, it seems that they will be the tellers of their story moving forward.

In the words of one Selk’nam living in Tierra del Fuego, “…we have not died. But we have changed. We are alive, and we are here, right here.”

Leave a comment