“You’re from Brazil? That’s amazing, you’re so lucky, it has such beautiful beaches!”

This was the oft-repeated phrase we would hear when I introduced Marilia to people early on in our relationship.

Admittedly, I’m surprised these comments weren’t accompanied by descriptions of monkey butlers regaling them with jungle stories.

To be fair, and more kind-hearted, I wasn’t sure what to expect when I came down to Brazil, outside of orange juice being served at every meal.

Having spent a little more time in Brazil, I have a little better perspective of their day-to-day life, at least through the eyes of a gringo.

*****

A question I often get these days when talking to friends, whether past colleagues, childhood, or college friends is: “What the hell do you do all day?”

In short, “Whatever I want.” To be a bit more serious, much of the time in Brazil, when we’re not traveling, we’re hanging out with the family, running errands, cooking, washing dishes – as there are no monkey butlers, or at least not yet – or heading to local breweries, churrasscos, or going to samba bars (maybe some stereotypes are true).

One day, as the temperature approached 40 degrees Celsius and the humidity neared 100%, I decided to throw on some sliders – because my dead foot doesn’t allow me to wear Havaianas – and get some picoles for the family. Just another man in gym clothes and sandals in Brazil. While walking, I posted a story on Instagram, and one of our Brazilian friends simply commented “Suco do Brasil”, a term I had never heard before.

When I asked my wife about it (the literal translation is “The Juice of Brazil”), she replied, essentially, that it’s synonymous with daily life and what it means to be Brazilian.

*****

A short warning for people who cannot be objective about history.

Before we dive into the next section, I’d like to paraphrase a free walking tour guide in Seville, Spain. “History is not good or bad, nor something to shy away from. It is reality.” It is also something that we all must learn from, so we don’t repeat the same mistakes (I don’t think many our current world leaders have studied history). I also want to note that while I love learning about history, this is not intended to be an academic paper, so, there are probably some small errors.

Slavery, much like the majority of the world at one time, was a driving force of the first several hundred years of what has come to be known as Brazil. In fact, it was to an order of magnitude much greater than the United States, and it was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to outlaw slavery. I highlight Western Hemisphere as there are still many parts of the world today where slavery exists, whether in its traditional form or state-sponsored indentured servitude, and I suggest all readers to learn more about this.

This complex history helps explain the modern landscape—leading to intricate racial relations, a remarkably diverse population mix, and, for many, an ongoing identity crisis. Understanding this backdrop provides essential context for the stories that follow.

Why are you writing about slavery? Simply bear with me for a little longer.

When the U.S. “outlawed” slavery (I don’t think I need to explain the use of quotations or italics), Brazil established an early marketing campaign for slave owners in the U.S. to emigrate to Brazil. This was important to Brazil for many reasons, one of the most important being agricultural technology, which was the IP of the day.

A large American settlement was created about 30 miles from Indaiatuba, in a town called Americana, near where my father-in-law was born.

Americana has a unique and complicated history. There is what amounts to a confederate cementary, complete with a stone monument honoring those that are lost, a museum of the towns history, which is like any other museum until you dig into said history, a rock-a-billy scene that’s heavily tied to the confederate flag, and, until 2020, an annual ‘southern heritage’ (that’s U.S. southern heritage) parade – there are some things I can get behind getting cancelled.

Before assumptions are made about my wife’s family, this is where the story begins to turn.

In 1888, Brazil formally outlawed slavery, and while these people were now ‘free’, the government did not want this population to be the face of Brazil, and former slave owners did not want to pay former slaves a wage for their work.

This led again to a variety of campaigns, incentives, and Brazil paying for transatlantic passage, to encourage migration, this time aimed at Europeans, in what is delightfully deemed as Brazil’s “white-ification stage”. These campaigns led to the creation of towns with massive European influence, ranging from Holland, Italy, German, and of course Portugal. In a brief reprise of a serious topic, my Fondue in the small, mountain town of Monte Verde was much better – and 4x cheaper – than my Fondue at one of the most well-known restaurants in Zurich.

While some Europeans came with the promise of status and wealth, others simply sought employment and a better life. The official ending of slavery came with a large influx of Italian immigrants to work the farm jobs. Between land owners not wanting to employ Blacks, and Italians undercutting the wages the Black population wanted for the same jobs, Italians became indentured servants in a form of semi-slavery, with no access to medical care, no schools, and physical abuses, which ultimately led to the Prinetti Decree, where Italy forbade any sponsored (paid) immigration to Brazil.

All of this leads us to December, 1945, when Jose Roberto Guedes de Oliveira was born, the grandson of one of those early Italian immigrants.

Jose Roberto Guedes, or simply Guedes, my father-in-law, is one of the happiest, kindest, driven, and intelligent people I’ve met.

His life has been one of self-determination and personal growth.

At the age of 9, Guedes started to contribute to the the family by having small jobs around town. By age 12, after losing both of his parents, he began selling candies to fully support himself and his family as the youngest child. Through this grit and by having one of the most joyous personalities I’ve seen (maybe with the exception of John Prine interviews), Guedes met his wife, raised a family, had a successful career, and received dual post graduates in law and economics from one of the premier universities in Brazil.

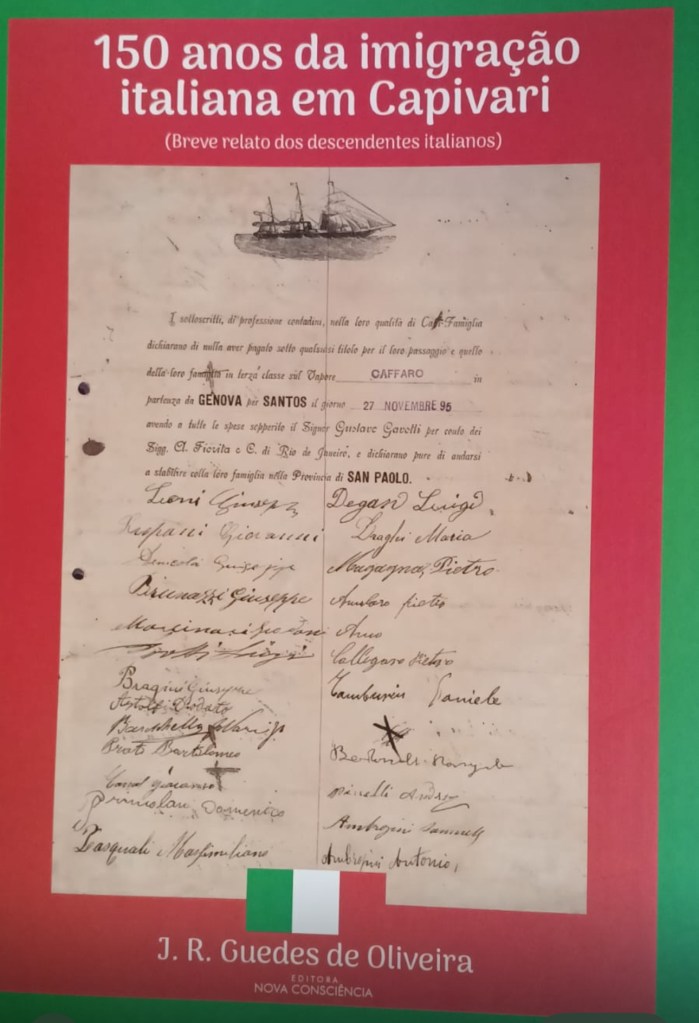

If this wasn’t enough, he has written and published nearly 40 books; mainly about local history of his region and biographies of noteworthy citizens. His latest published book is about Italian immigration in Brazil, and upon my arrival, the first boxes of these books arrived at the Rodrigues Oliveira household.

One of Guedes’ traditions is to hand out copies of his latest book around town, and so, on a day in March, we drove to his home town of Capivari and neighboring areas (including Americana), both to complete this task, show me where he grew up, and visit the American Heritage Museum.

What followed was a day of joy and nostalagia.

We were able to stop at my father-in-laws childhood home, the interior reminiscent of a New Orleans shotgun house, which had been converted into a sewing store. The owners welcomed us in, spoke, and listened to him for 30 minutes, intently and with a genuine sincerity. While we were in the doorway, a giant grasshopper managed his way in, and Guedes gently scooped him up and placed it outside in a nearby tree.

Next, we made our way to a bakery he frequented growing up, and while speaking with the owner, a childhood friend stopped in. Guedes and her caught up for awhile (or briefly, if you’re Brazilian), introduced Marilia and I, then we were on our way.

Our last stop was at a local butcher to pick up some linguiça for dinner that night. As it was near closing time, most of the meat had been sold, and candidly, I was distracted by the freezer filled with picoles, hoping to find my coveted Milho.

Then, a moment so genuine happened that one would think they were watching a Hallmark movie.

Guedes had struck up a conversation with the butcher, detailing his book. Nearby, a slender elderly man of a similar age was sitting down, and interrupted Guedes. His grandfather had emigrated from Italy, and wondered about the book. Guedes asked the name of his grandfather, and after thumbing through some pages, he pointed to a photo of a list of names.

In his research, Guedes had found original immigration records and included to photos of these lists in his book. The name he was pointing to, was in fact, the mans’ grandfather, and he began to softly cry. Guedes handed him the book to keep.

*****

As we drove back to Indaiatuba, there were cracks in Guedes’ voice, which was usually one of unwavering joy, and a glint in his eyes, no doubt remembering the events of his 80-plus years that had led him to this day, and perhaps wondering where all the time had gone.

While many of us cannot comprehend this feeling, one day we all likely will, and I hope at least that Guedes knows the positivity he has given to this world.

*****

So, what is O Suco Do Brasil? The juice of Brazil is: setting up your own plastic chairs at a brewery with a friend and talking about tech. It’s negotiating Uber routes with your driver because that’s the way it is. It’s walking to get popsicles on a hot summer day in January, or eating a sushi with smashed Doritos mixed in with the rice. It’s figuring out that Cariocas are Miamiams and Paulistas are New Yorkers. It’s helping sua sogra and doing your daily chores of washing dishes, or cooking Massaman curry for the family to show them a different part of the world.

And sometimes, it’s seeing a moment that transcends languages and cultures, and understanding the humanity in a people that you knew next to nothing about a short time ago.

Cheers.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply